Thirty years ago in a shipyard on the North coast of Poland, Communism began to fall. Today, Gdańsk shipyard is more likely to host a rock concert than a political meeting and the locals are more concerned about whether the new football stadium will be ready in time for Euro 2012, but the city will forever be associated with the Solidarity movement. As Poland celebrates this anniversary and remembers the impact Solidarity had (and continues to have) in transforming the country from a Soviet satellite state into a fully-functioning EU democracy it is worth asking if similar movements could be as effective across the former U.S.S.R and even further afield.

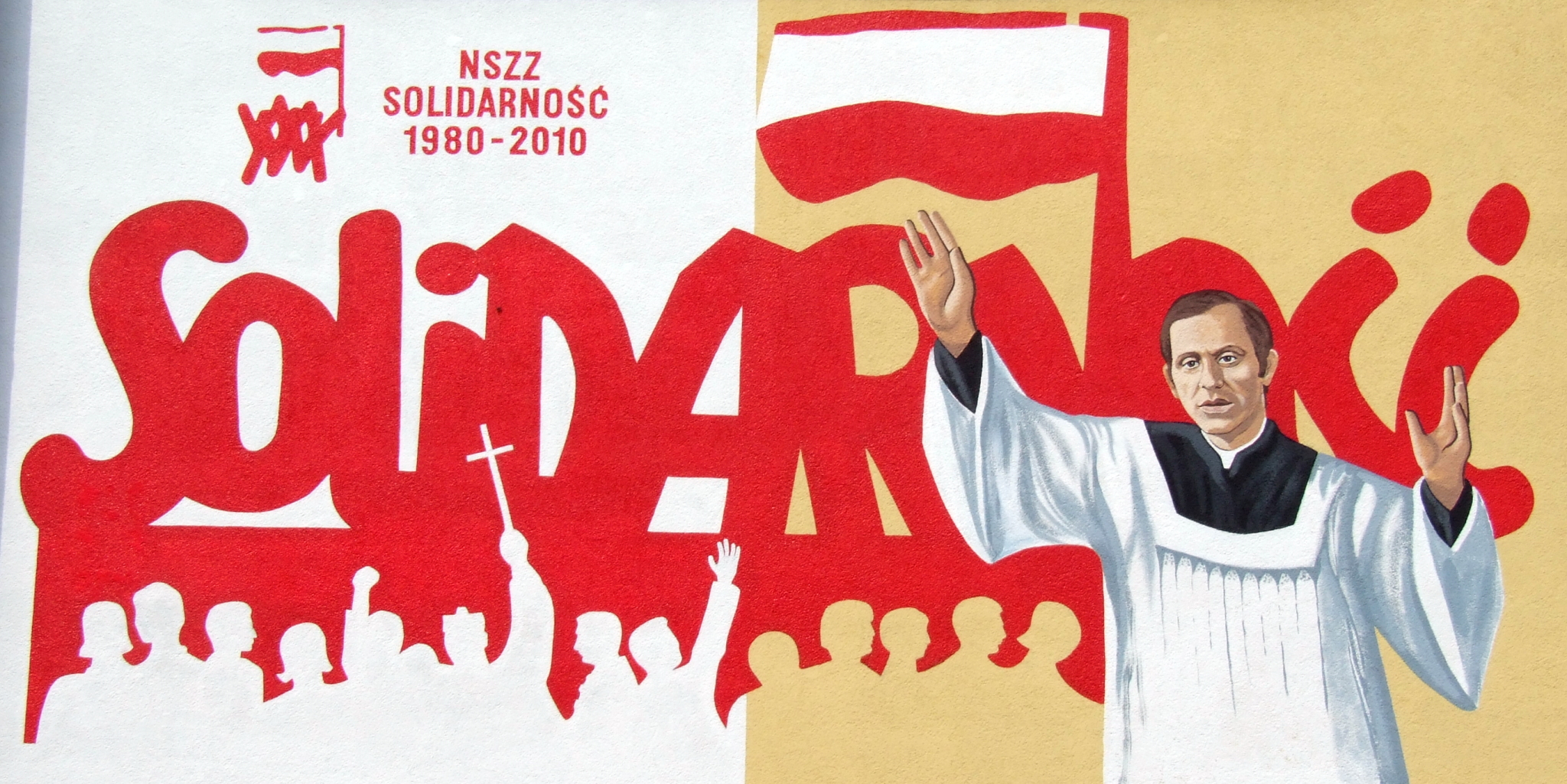

For those who don’t know, Solidarity was founded in 1980 as a response to the political and social difficulties faced by the Polish government and which plagued the everyday life of Poles across the country. It became the first trade union in the Eastern Bloc that was not controlled by the Communist Party and despite continued attempts to repress and even destroy the group throughout the 1980s; Solidarity grew as a political force and earned the right to contest the 1989 semi-free elections through the Polish Round Table Agreement. As a new and legitimate political party, the group won 160 of the 161 seats available and Solidarity co-founder Lech Wałęsa became the President who presided over the collapse of Communism in Poland. Since the early 90s though, Solidarity has become more of a trade union in the more traditional sense of the word and has little political influence as a party.

Wałęsa unfortunately did not attend the celebrations for reasons that varied from ill-health to making a point against the current political affiliations of the union. However, U.S. President Barack Obama did send a message of support that was read out by the American ambassador to Poland, Lee Feinstein: "Through the Solidarity movement, the people of Poland reminded us of the power each of us has to write our own destiny. In the face of tyranny and oppression, they chose freedom and democracy and, in doing so, changed their country and the course of history." This raises an important point; Solidarity was always more than just a political party or even a trade union but was a social movement that brought the people of the country together against the U.S.S.R.

Solidarity was strongly influenced by Catholic Social Teaching which is unsurprising given that even today more than 88% of people belong to the Catholic Church. Furthermore, the Pope at the time, John Paul II, was Polish and in a major document called ‘Sollicitudo Rei Socialis’ supported the concept of solidarity. More importantly though, the movement was underpinned by the philosophical teaching of Leszek Kołakowski who concluded in his Theses on Hope and Hopelessness that “the best way to counteract prosecutions is massive committal....thus in the countries of socialist despotism, those who inspire hope are also the inspirers of a movement which could make this hope real”. Or, as it was put in Kołakowski’s obituary: “self-organised social groups could gradually expand the spheres of civil society in a totalitarian state”.

A big idea and one that retains its importance even today for many countries where groups seek social change; especially when we look at the types of state described. Kołakowski speaks of states which have destroyed historical memory, manipulated all information and where memory has been nationalised so that citizens have been robbed of their identity. This could be used to describe a worryingly large number of countries in 2010, including many post-Soviet Republics. In fact of the 15 post-Soviet states, the organisation Freedom House has declared eight not to be free, three to be partially free and only four are considered to be free states.

Some offenders are worse than others though and ought to be highlighted as such. Turkmenistan continued to be controlled by the Communist Party after 1991 and the country soon became isolated and the media strictly controlled. The President died in 2006 and whilst his successor, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, promised reforms including a new constitution, in reality there has been little political reform and most political dissidents are locked up. Meanwhile in neighbouring Uzbekistan, Islam Karimov has been President since 1991 and since then he has stripped all other institutions of any meaningful power and there is no effective opposition. Finally we have Belarus whose President, Aleksandr Lukashenko, has been described as ‘Europe’s last dictator’ as opposition is crushed with violence, harassment and intimidation.

The people of these countries, and others like them could learn a lot from the teachings of Kołakowski and the way they were put into practice by Wałęsa. The path to freedom is often long and arduous but the story of a fired electrician in a Polish port becoming President ought to be one that inspires people all these years later and there are indeed modern day examples. The Dalai Lama in Tibet, Morgan Tsvangirai in Zimbabwe and Aung San Suu Kyi in Burma are all people who deserve our support in the way that Solidarity received widespread support in the 1980s. Wałęsa may not have attended the celebrations at the weekend but that doesn’t mean we have nothing to thank him for and can’t still learn from him today.